Takahichi’s Media Rebellion: The Fall of TV Politics and Rise of Direct Democracy

The Day Japan’s Media Froze — When Takahichi’s Silence Spoke Louder Than Words

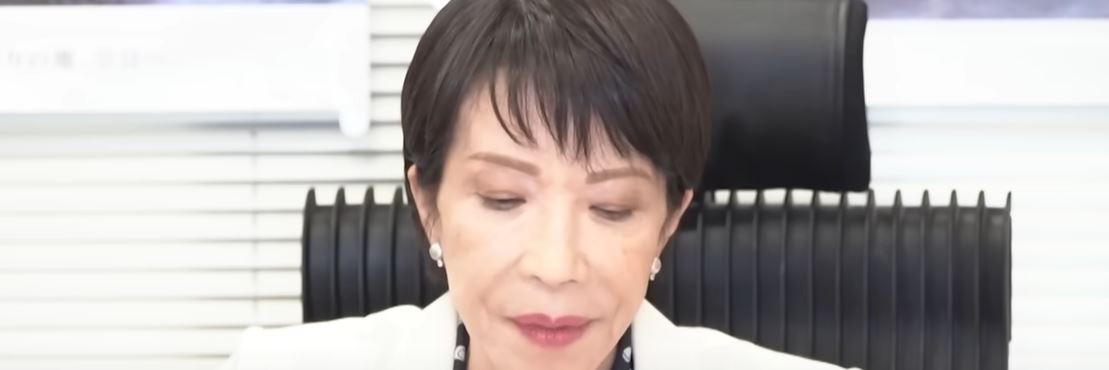

On October 10, 2025, Japan’s political and media landscapes froze in collective shock. Just moments before live broadcasts were set to begin, Prime Minister Sanae Takahichi abruptly cancelled her scheduled appearances on three major TV networks — TBS’s News N Star, Fuji TV’s Mr. Sunday, and NTV’s News Every. The cancellation came less than ten minutes before airtime, sending every newsroom into chaos.

Producers scrambled, announcers hesitated, and cameras kept rolling on empty studio chairs. In an age when “live” equals “truth,” the sudden silence of one of Japan’s most powerful politicians raised a question no one expected: what happens when a leader refuses to play by television’s rules?

For decades, TV was the central stage of Japanese democracy — the place where political messages were filtered, framed, and fed to the public. But that day, something fundamental broke. Takahichi’s decision was not a simple act of defiance; it was a symbolic declaration that the balance of power between politicians and media had shifted.

Her silence became louder than any statement. As viewers flooded social media with reactions, one phrase began trending across platforms: “She finally broke free.” What many saw as a scandal, others hailed as a moment of liberation — a rejection of manipulated narratives and a step toward unfiltered, direct communication between leaders and citizens.

This article explores why Takahichi’s “media blackout” matters far beyond politics. It marks the beginning of a new era where television no longer defines truth, and where every citizen must choose — will you trust the screen, or the source?

The Media Shock — Why the TV Networks Panicked

When Takahichi’s team called the three major TV networks only ten minutes before airtime, the message was brief but devastating: “All appearances are cancelled.” For TBS, Fuji TV, and NTV, it was more than an inconvenience — it was a catastrophe. In the fast-paced world of live news, schedules are sacred. Scripts are written, questions rehearsed, lighting adjusted, and every second is measured with precision. A sudden withdrawal of a prime guest, especially the ruling party leader, is equivalent to an air disaster in broadcasting terms.

Inside the studios, chaos erupted. Producers shouted over headsets, anchors exchanged confused glances, and political correspondents tried desperately to confirm what had gone wrong. Had there been an accident? Was there political pressure from rival factions? Or had the Prime Minister simply declared war on the media establishment itself? The air was thick with speculation.

As the broadcasts began without her, anchors were forced to fill the void with awkward statements such as: “Due to unforeseen circumstances, Prime Minister Takahichi will not be appearing.” It was a sterile explanation for a moment that shook Japan’s information ecosystem. For decades, no top-level politician had ever refused all major networks on the same night.

What made the panic worse was timing. The cancellation came just hours after Takahichi had announced the official end of the long-standing coalition between the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its partner party. In other words, this was not merely a scheduling issue — it was a direct disruption of the nation’s primary communication channel between government and citizens.

The networks feared something greater than a lost interview: a loss of control. Television had long been the gatekeeper of national conversation — deciding what to air, which soundbites to highlight, and how to shape public emotion. But on that night, their authority evaporated in real time. The stage was set for a confrontation between the old media empire and the new age of direct communication.

Within minutes, Twitter (X) and YouTube exploded with comments: “Good move!” “Finally, a politician with backbone.” While TV staff panicked, the internet celebrated. And that, more than anything else, revealed the truth: Japan’s audience had already shifted its loyalty — from broadcasters to broadband, from anchors to algorithms, from television to trust.

A Silent Rebellion — What Her Refusal Truly Meant

At first glance, Takahichi’s last-minute cancellation seemed reckless — a political misstep that risked alienating mainstream audiences. But as the dust settled, analysts and citizens alike began to see a deeper message behind the silence. Her refusal was not an escape from accountability. It was a statement of independence — a rebellion against a media system that many believe has long traded truth for theatrics.

For years, Japanese politicians have viewed television as both a necessity and a trap. Every word spoken on air is subject to selective editing, every gesture dissected for emotional cues. The goal of many programs is not to inform but to entertain — to generate debate, not dialogue. In that environment, authenticity becomes impossible. Takahichi’s decision to withdraw from the stage was a way of saying: “I will not be scripted.”

Her silence exposed a truth the public already felt: that live television is rarely “live” in spirit. Timing, camera angles, captions, and music all subtly guide viewers toward a predetermined emotional response. A politician who raises her voice can be made to appear “angry.” A firm answer can be framed as “arrogant.” Even a neutral statement can be edited to fit a desired narrative. In short, the broadcast becomes a performance — and the politician, an unwilling actor.

By walking away, Takahichi dismantled that illusion. Her act of non-appearance became an act of resistance — a refusal to participate in the theater of controlled perception. And in doing so, she transformed absence into presence. The missing figure on the TV screen said more about truth and manipulation than any televised speech ever could.

The public response revealed a generational divide. While many older viewers were stunned, younger audiences — raised on YouTube and TikTok — instinctively understood her reasoning. They had long suspected that mainstream broadcasts were designed to provoke emotions rather than deliver clarity. To them, Takahichi’s silence was not cowardice. It was courage — a refusal to let others dictate her voice.

In hindsight, her decision marked a turning point in Japanese politics. It signaled that the age of mediated messaging is fading, and that politicians can now bypass broadcasters entirely. Through platforms like X (Twitter), YouTube, and Instagram, leaders can speak directly to the people, uncut and unfiltered. What once required a television studio can now be done with a smartphone. That shift is not just technological — it is ideological. It redefines who controls the narrative.

How Television Lost Its Power Over Politics

For more than half a century, television was the throne of political influence in Japan. It crowned leaders, shaped reputations, and decided elections. To appear on the evening news meant legitimacy; to be ignored meant invisibility. But that hierarchy has crumbled. What happened on October 10, 2025, was not the cause of that collapse — it was its confirmation.

Television once held absolute control because it owned the gateways of information. Politicians needed reporters, cameras, and studio invitations to reach the public. In return, broadcasters dictated the format, tone, and timing of communication. It was an unspoken deal: exposure in exchange for editorial submission. But as digital technology democratized access to audiences, the foundation of that deal began to erode.

The rise of smartphones, streaming platforms, and social media dismantled TV’s monopoly on attention. People no longer waited for the 7 p.m. news to understand the world — they opened their feeds and found dozens of perspectives in real time. Each tweet, post, and video became a micro-broadcast. And as audiences diversified, the old media’s centralized authority began to fade into irrelevance.

Television’s slow decline was accelerated by its own rigidity. While digital creators experimented with direct engagement and transparency, networks clung to their traditional scripts — panel debates, controlled segments, and staged confrontations. The format that once symbolized professionalism started to feel artificial. Younger viewers tuned out. Older viewers, once loyal, grew skeptical. Even credibility — television’s final defense — began to erode under the weight of biased framing and sensational headlines.

By 2025, social media had become the new “press conference.” Politicians launched campaigns on X, livestreamed policy discussions on YouTube, and posted unfiltered commentary on Instagram. The message was clear: control had shifted from newsroom editors to content creators. And with that shift came a new kind of authenticity — imperfect, spontaneous, but undeniably real.

Takahichi’s rejection of television wasn’t rebellion in isolation; it was alignment with reality. She simply acted on what data had already proven — that the Japanese public now consumes politics through screens they hold, not the ones mounted on their walls. The medium of power has changed, and television’s age of political dominance has ended. What remains is a question of adaptation: Can traditional media evolve before it becomes obsolete?

The New Era of Political Communication — From Broadcasts to Direct Dialogue

The moment Takahichi stepped away from television, she stepped into history. Her silence on national broadcasts became her first words in a new language — the language of direct digital communication. In this new era, political leaders no longer depend on studio lights or professional anchors. They depend on connection, immediacy, and trust.

Through platforms like X (formerly Twitter), YouTube, and Instagram, politicians can now reach millions without intermediaries. They can livestream policy announcements, respond to citizen questions in real time, and clarify misinformation before it spreads. The era of waiting for tomorrow’s newspaper headline is over. Now, politics moves at the speed of Wi-Fi.

This shift has redefined the relationship between leaders and voters. In the broadcast era, communication was one-way — politicians spoke, citizens listened. Today, it’s a dialogue. Comments, reactions, and reposts form an instant feedback loop. Supporters amplify messages, critics challenge them, and journalists chase the digital trail. Every post is both statement and conversation.

The power of this transformation lies in its authenticity. When a leader speaks through their smartphone camera — unscripted, unedited, and unfiltered — the audience perceives honesty. Even minor imperfections, like shaky video or casual speech, create a sense of humanity that polished TV productions rarely achieve. It’s the difference between being “seen” and being “understood.”

However, this freedom comes with new responsibilities. Without professional editors, politicians must fact-check their own statements. Without time delays, emotional remarks can instantly go viral — for better or worse. And without the safety net of producers, the burden of clarity rests entirely on the speaker. This is communication without training wheels.

Yet, for Takahichi and a growing generation of digital politicians, that is precisely the point. They prefer accountability to authenticity. They believe that citizens deserve access to raw, unfiltered truth — even if that truth is imperfect. In doing so, they’re reshaping Japan’s democratic dialogue, transforming political communication from a broadcast performance into a shared, ongoing conversation between equals.

From Viewers to Participants — The Rise of Information Literacy

The most profound outcome of Takahichi’s media rebellion was not political — it was cultural. By refusing to appear on television, she forced citizens to ask themselves a fundamental question: “Where does my truth come from?” In an age of information overload, this question defines the difference between manipulation and awareness.

For decades, the Japanese public played the role of viewers — passive recipients of televised narratives. Networks decided what mattered, which images to show, and how long each issue deserved attention. Citizens consumed information the way they consumed entertainment: without the power to intervene. But the digital revolution shattered that dynamic. Now, anyone with a smartphone can fact-check, analyze, and publish within seconds.

This democratization of information has birthed a new civic skill: information literacy. It’s no longer enough to read or watch; one must interpret. Who created this content? What perspective does it represent? Is it evidence-based or emotionally framed? These are no longer academic questions — they are survival tools in the modern information ecosystem.

Social media has accelerated this shift by transforming every citizen into both consumer and creator. When a politician posts on X or YouTube, the audience doesn’t just absorb the message — they respond, remix, and redistribute it. Through this process, information becomes collaborative, and collective analysis replaces passive consumption. The line between journalist, citizen, and critic has blurred beyond recognition.

However, empowerment brings risk. The same tools that enable participation also amplify misinformation. False quotes, edited videos, and algorithm-driven outrage can distort perception faster than truth can recover. That’s why information literacy is more than a skill — it’s a civic responsibility. Citizens must learn not just to read information, but to interrogate it.

In this new reality, education systems, media institutions, and governments must adapt. Teaching people how to think critically about information is as essential as teaching them how to read and write. Just as past generations learned to navigate printed text, today’s generation must learn to navigate the digital torrent — to distinguish facts from feelings, and evidence from emotion. Only then can democracy survive the noise.

Takahichi’s silent protest, whether intentional or not, ignited this transformation. By removing herself from the broadcast frame, she placed the responsibility of truth on the audience. She reminded Japan that democracy is not a show to be watched, but a conversation to be joined. And in that realization, the viewer became a participant.

Conclusion — The End of Broadcast Politics and the Dawn of Direct Democracy

The events of October 10, 2025, will be remembered not just as a media scandal, but as a milestone — the day when Japan’s political communication crossed a historic threshold. Takahichi’s refusal to appear on national television was not an act of arrogance. It was a declaration that the age of broadcast politics is over.

For decades, political power and media power were inseparable. Politicians needed the camera, and the camera needed the politician. Together, they constructed a carefully staged version of democracy — polished, edited, and controlled. But in an era when every citizen carries a digital screen in their pocket, that arrangement no longer holds authority. The monopoly of televised truth has collapsed.

In its place rises a new form of governance — a system grounded in transparency, interaction, and immediacy. Citizens no longer wait for information; they seek it. They question, verify, and respond in real time. Democracy, once mediated through screens, now happens within them. This is not chaos — it is evolution.

The implications are profound. Television’s loss is not merely technological; it’s philosophical. It forces society to confront what “truth” means in a world without filters. It demands that individuals assume responsibility for interpretation, and that leaders speak with clarity rather than performance. The balance of communication has shifted from broadcast control to shared accountability.

Of course, the digital democracy that follows will not be perfect. It will be messy, emotional, and unpredictable. False information will spread faster than facts, and algorithms will tempt people into echo chambers. But despite those risks, the new paradigm is more democratic than its predecessor. It gives voice to everyone — not just to those invited into the studio.

Takahichi’s “silent speech” has become a symbol of this transition. She reminded Japan that communication is no longer about visibility, but about authenticity. By rejecting the old media stage, she gave birth to a new one — a digital agora where politicians and citizens meet on equal ground.

The end of broadcast politics is not the end of democracy. It is its rebirth. In this new age, the power to define truth no longer belongs to networks or governments. It belongs to the people — to those who question, who verify, and who choose to listen with intention. And that, perhaps, is the most revolutionary silence in modern Japan.

ディスカッション

コメント一覧

まだ、コメントがありません