Breaking News: Japan Innovation Party Demands 50-Seat Cut in Parliament

Introduction: A Coalition Negotiation at a Crossroads

Japan’s political stage is facing a turning point as the Japan Innovation Party (Ishin) demands a drastic reform before forming a coalition with the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). The central issue is bold and controversial — a proposal to cut 50 seats from the House of Representatives. This move aims to streamline Japan’s legislative structure and restore public trust in politics, yet it raises deep concerns over fair representation.

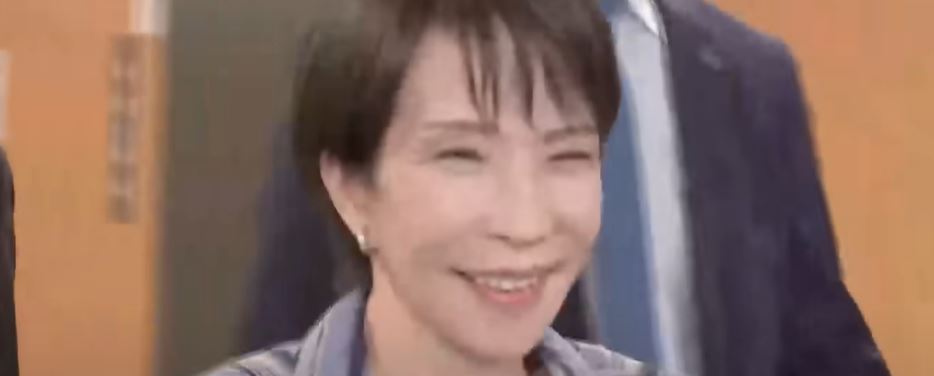

Ishin’s leader, Hirofumi Yoshimura, has made it clear that without an agreement on both the scale and timeline of seat reduction, his party will refuse to join the coalition. This uncompromising stance has injected new tension into ongoing coalition talks, highlighting a fundamental clash between reform-driven politics and the preservation of parliamentary balance.

While some see the proposal as a long-overdue step toward a leaner, more efficient government, others warn it could erode democratic diversity by sidelining smaller parties. As Japan prepares for the upcoming extraordinary Diet session, the debate over how to balance representation and reform is set to dominate the political agenda.

This article explores the roots, rationale, and repercussions of Ishin’s demand — examining whether Japan’s call for political efficiency can coexist with its democratic values.

The Core Demand: Cutting 50 Seats from Japan’s Lower House

At the heart of the ongoing coalition talks lies the Japan Innovation Party’s (Ishin) uncompromising demand: a 50-seat reduction in Japan’s House of Representatives. This proposal, announced by party leader Hirofumi Yoshimura, represents one of the most ambitious parliamentary reform initiatives in recent years. Ishin argues that Japan’s legislature has grown inefficient and detached from the public, and that a smaller, more accountable parliament is essential to rebuilding political trust.

Currently, the House of Representatives holds 465 seats, and Ishin’s plan would bring that number down to approximately 415. Yoshimura insists that this reform must not remain a symbolic debate but be tied to a specific implementation schedule. He has publicly declared that without such commitment, Ishin will not participate in any coalition government led by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

The party’s rationale is straightforward: fewer legislators mean less taxpayer burden and a clearer line of accountability. Ishin emphasizes that Japan’s political system, burdened by bureaucracy and overrepresentation of rural districts, requires a structural overhaul. By cutting 50 seats, the party claims, legislative efficiency would increase while wasteful spending would decrease — aligning with Ishin’s core values of transparency, reform, and fiscal discipline.

However, Yoshimura’s approach also serves a strategic purpose. By framing the debate around reform, Ishin positions itself as the only major party capable of challenging the LDP’s dominance while appealing to public frustration with “political stagnation.” This move could redefine coalition dynamics, pushing Japan toward a new era of competitive and reform-oriented politics.

Why Ishin Prioritizes Parliamentary Reform

The Japan Innovation Party’s (Ishin) obsession with parliamentary reform is not new. Since its founding, Ishin has promoted a vision of a “lean government” — one that minimizes waste, eliminates bureaucratic inefficiency, and restores accountability to taxpayers. The call to reduce parliamentary seats is a direct extension of this philosophy, representing not only a policy demand but also a core identity of the party’s reformist DNA.

For Hirofumi Yoshimura, Ishin’s leader, reform is both an ideological and strategic imperative. He has repeatedly emphasized that Japan’s postwar political system is “outdated,” dominated by entrenched party interests and excessive public expenditure. Yoshimura’s message resonates strongly with younger voters and urban professionals who are increasingly frustrated with traditional politics. By pushing for bold structural change, Ishin seeks to position itself as the only genuine alternative to the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

The timing of this demand is equally significant. As Japan faces demographic decline, an aging population, and regional disparities, Ishin argues that smaller government is the only sustainable path forward. The proposed seat reduction symbolizes efficiency and modernization — ideas deeply rooted in the party’s origins in Osaka, where Ishin first gained popularity through local administrative reforms and cost-cutting measures.

Furthermore, by making parliamentary reform a precondition for coalition talks, Ishin sends a clear message: it will not compromise on principles for political convenience. This uncompromising stance strengthens its image as a “principled reformer” in contrast to parties often criticized for backroom deals and indecisive policies. The approach may limit Ishin’s short-term coalition prospects, but it reinforces long-term credibility as a reform-driven force within Japanese politics.

Opposition Voices: Fear of Weakened Democracy

While the Japan Innovation Party (Ishin) promotes its plan as a step toward efficiency and accountability, opposition lawmakers and political analysts warn that the 50-seat reduction could endanger Japan’s democratic balance. Critics argue that fewer seats would mean fewer opportunities for minority voices to be represented in the House of Representatives, potentially solidifying the dominance of large parties like the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

Smaller parties, including the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) and the Japanese Communist Party (JCP), have voiced concerns that the proposed cut would disproportionately affect opposition districts, especially urban areas where new and smaller parties tend to gain support. A smaller legislature, they argue, may lead to an even stronger two-party structure and reduce the diversity of debate within the Diet.

Political experts also highlight that Japan’s electoral system already faces challenges in ensuring proportional representation. With population decline accelerating in rural regions, each seat already represents an increasing number of voters. Reducing the total number of lawmakers, they claim, would further dilute the value of each vote — creating a system where citizens in less populated areas hold relatively more power than those in metropolitan centers.

Public opinion on the issue remains divided. While some citizens support the idea of cutting political costs, others fear that such a move is more symbolic than substantial. Opponents argue that without reforms to campaign finance transparency, lobbying regulations, and bureaucratic oversight, simply reducing seats would do little to improve political integrity. In this view, Ishin’s reform may risk turning into an “efficiency illusion” rather than genuine democratic progress.

Ultimately, the opposition frames the debate not as a fight over numbers but over principles: whether Japan values cost-cutting efficiency more than pluralistic democracy. This question will likely dominate parliamentary discussions in the upcoming extraordinary session.

Supporters’ View: Efficiency and Global Perspective

Supporters of the Japan Innovation Party’s (Ishin) proposal argue that reducing the number of lawmakers is a logical and overdue step toward making Japan’s government more efficient. They claim that the 50-seat reduction would not weaken democracy but rather modernize a political system that has become bloated and resistant to change. For many, this reform symbolizes a shift from political complacency toward practical governance.

One of the strongest arguments in favor of Ishin’s plan comes from international comparison. Japan currently has 465 members in the House of Representatives — significantly fewer than many major democracies when adjusted for population. For instance, the United Kingdom has 650 members in the House of Commons, and Germany’s Bundestag often exceeds 700 seats. Even after a 50-seat reduction, Japan’s parliament would still maintain a higher representative ratio than most developed nations.

Proponents emphasize that a smaller legislature could streamline decision-making and reduce redundant committees, leading to faster policy implementation. They also point to the growing public demand for fiscal discipline. With rising national debt and an aging population, taxpayers are increasingly critical of political inefficiency and excess spending. A leaner Diet, supporters argue, would demonstrate the government’s willingness to share the burden of reform with the public.

Some policy experts further contend that a reduced parliament could foster a new generation of “policy-focused” politicians rather than career legislators. By decreasing the number of available seats, elections could become more competitive, incentivizing candidates with strong expertise and innovative ideas rather than those relying on legacy support or political inheritance.

Ultimately, advocates of Ishin’s proposal view it as a test of Japan’s ability to evolve. In their eyes, efficiency does not equal exclusion — it means optimizing representation to match the realities of modern governance. They believe that fewer, but more capable, representatives could strengthen rather than weaken Japan’s democracy in the long run.

Political Implications for Coalition Building

The Japan Innovation Party’s (Ishin) insistence on a 50-seat reduction has transformed what began as routine coalition negotiations into one of the most consequential power struggles in recent Japanese politics. The ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) faces a dilemma: accept Ishin’s radical reform proposal and risk alienating its own rural base, or reject it and forgo the potential stability that a coalition could bring.

Behind the scenes, LDP strategists are weighing the political costs. Many conservative lawmakers are skeptical of Ishin’s plan, fearing that reducing seats would erode representation in rural constituencies — regions that have long served as the LDP’s electoral backbone. Accepting Ishin’s demand could therefore disrupt the delicate balance between reform and preservation that has defined the LDP’s postwar dominance.

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party for the People (DPP) has expressed clear support for Ishin’s reform push. By endorsing the proposal, the DPP aims to position itself as a bridge between reformist and establishment forces. Some analysts suggest that this alignment could open the door to a three-party cooperation framework, particularly on fiscal reform and government downsizing initiatives.

However, political observers caution that Ishin’s hardline stance may limit its negotiating flexibility. Coalition talks in Japan often rely on compromise and behind-the-scenes bargaining, yet Ishin’s “all or nothing” approach leaves little room for incremental progress. While this boosts the party’s credibility among reform-minded voters, it may also isolate Ishin from the mainstream coalition-building process.

As the extraordinary Diet session approaches, the stakes are high. If the LDP concedes even partially, it could mark the beginning of a new era of reformist politics in Japan. If not, Ishin may leverage public opinion to strengthen its position in the next general election. Either way, the debate over parliamentary reform is now inseparable from the broader question of how Japan will balance stability and transformation in its political future.

Conclusion: Can Japan Balance Representation and Reform?

As the debate over parliamentary reform intensifies, Japan finds itself standing at a critical crossroads. The Japan Innovation Party (Ishin) has reignited a long-dormant national discussion about how political representation should function in a modern democracy. Its proposal to cut 50 seats from the House of Representatives is more than a structural adjustment — it symbolizes a fundamental challenge to the way political power has been distributed for decades.

The reform’s supporters see it as a step toward efficiency, fiscal responsibility, and a revitalized trust between citizens and the state. They believe Japan must streamline its political system to reflect a shrinking population and mounting economic pressures. On the other hand, critics warn that such reform risks weakening minority voices and undermining pluralism — both essential pillars of democracy.

What makes this debate especially significant is its timing. Japan is grappling with demographic decline, rising social inequality, and voter apathy. The question is no longer just about how many lawmakers the Diet should have, but whether Japan’s political system can adapt quickly enough to reflect the country’s evolving needs. In this sense, Ishin’s proposal has already succeeded in forcing a broader national reckoning about what democracy means in the 21st century.

Regardless of whether the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) accepts Ishin’s conditions, the issue will likely remain central in Japanese politics for years to come. The push for “fewer but stronger representatives” challenges old assumptions about power and representation. For Japan to balance reform with democracy, it must find a model that values both efficiency and inclusion — ensuring that modernization does not come at the cost of democratic vitality.

In the end, Ishin’s demand may be remembered not merely as a coalition condition, but as a defining moment that forced Japan to reimagine the architecture of its political future.

ディスカッション

コメント一覧

まだ、コメントがありません