Japan’s Stand Against Chinese Tech Surveillance

Japan’s Growing Concern Over Chinese Surveillance Technology

In recent months, Japan’s political leaders and security experts have raised strong concerns about the use of Chinese-made technology within the country. From surveillance cameras to data storage systems, Chinese tech companies such as Tencent, Alibaba, and Huawei have increasingly become part of Japan’s infrastructure. However, lawmakers like Sanae Takaichi and Yoichi Takahashi are now warning that this growing dependence may expose Japan to serious national security risks.

Their warnings are not based on speculation. Under China’s Anti-Espionage Law, the Chinese government can legally demand access to data from any company headquartered in China. This means that any device or software connected to these systems could potentially transmit sensitive information back to Beijing. As a result, Japan’s security community is urging both government agencies and private companies to reconsider using certain Chinese technologies.

This article explores the reasons behind these warnings, the technological and political implications for Japan, and how the nation is preparing for a new era of data sovereignty and digital independence.

Understanding China’s Anti-Espionage Law and Its Impact on Japan

In July 2023, China expanded its Anti-Espionage Law, granting authorities broad powers to investigate and detain individuals suspected of “spying.” The law’s vague language means that even ordinary business activities—such as gathering market data or using cloud services—can be interpreted as espionage. This ambiguity has caused anxiety among foreign companies operating in China and Japanese citizens traveling or working there.

Under this legislation, any organization or individual is required to assist Chinese intelligence agencies upon request. This includes providing data, communication logs, or technical information. In practice, it allows the Chinese government to legally access data from private tech giants like Tencent and Alibaba. Such access raises major concerns about the confidentiality of Japanese government and corporate information stored on Chinese cloud platforms.

In recent years, several Japanese nationals have been detained in China under this law, often without clear evidence or explanation. These incidents highlight how the Anti-Espionage Law can be used politically, rather than purely for security. As a result, Japanese policymakers are reevaluating their reliance on Chinese technology and considering stricter domestic data protection and counter-espionage measures.

Ultimately, the law represents a turning point for Japan’s national security policy. It forces the country to balance economic cooperation with China against the urgent need to protect sensitive information and maintain technological sovereignty.

The Expanding Presence of Tencent, Alibaba, and Huawei in Japan

China’s technology giants have become deeply embedded in Japan’s digital ecosystem. Companies such as Tencent, Alibaba, and Huawei have built partnerships with Japanese corporations, universities, and even local governments. While these collaborations promise lower costs and cutting-edge innovation, they also introduce serious national security risks.

Tencent, the owner of the popular messaging app WeChat, operates several data processing centers in Japan. Many small and medium-sized enterprises use its cloud solutions for business communication and file storage. However, cybersecurity experts warn that under China’s Anti-Espionage Law, Tencent could be compelled to share data with Chinese authorities—even if that data originates in Japan.

Alibaba Cloud has also expanded rapidly, offering affordable cloud computing services to Japanese startups. While cost-efficient, these services come with hidden vulnerabilities, such as potential backdoor access and weak encryption standards. This has prompted Japanese officials to caution businesses against storing sensitive data on foreign-owned platforms.

Huawei’s role is equally concerning. Despite being excluded from Japan’s government contracts in 2019, its hardware components remain widely used in surveillance cameras and communication devices. Experts like Yoichi Takahashi argue that even seemingly harmless hardware could be exploited to collect metadata, camera footage, or GPS information.

As a result, Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications has begun recommending that public institutions and major corporations audit their digital supply chains. The goal is clear: to minimize dependency on systems that could potentially compromise national data sovereignty.

What Japan’s Security Leaders Are Saying About Chinese Technology

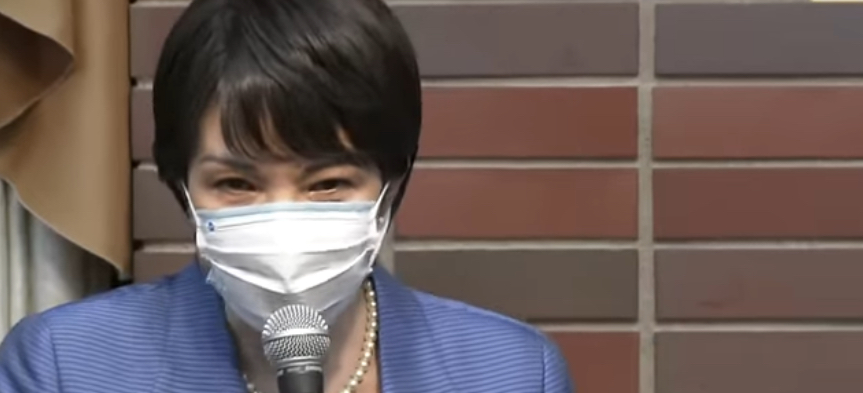

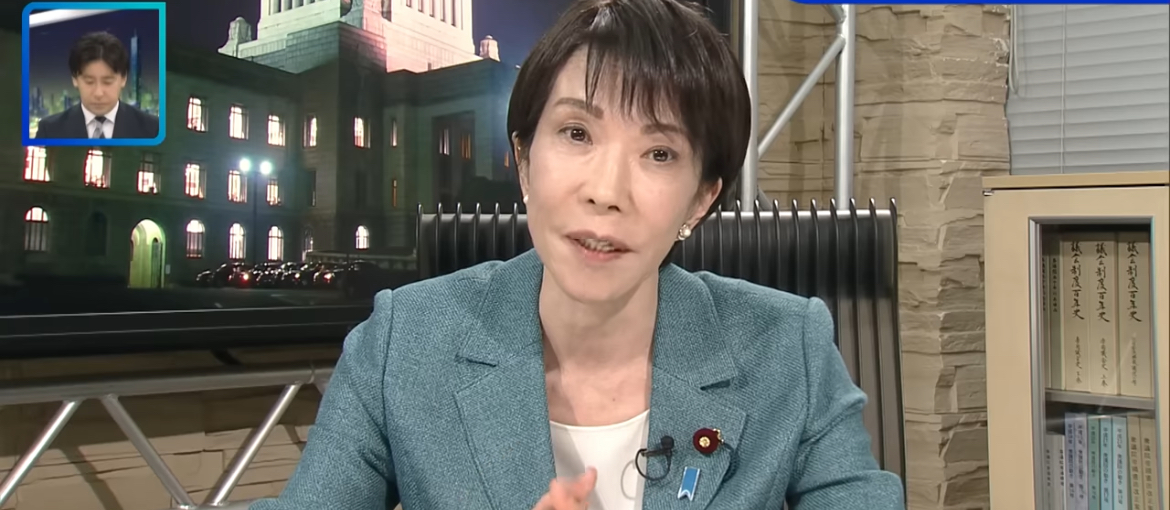

Prominent Japanese figures such as Sanae Takaichi, the Minister of Economic Security, and Yoichi Takahashi, an influential economist, have become vocal about the dangers of depending on Chinese technology. Both experts argue that Japan must recognize China’s surveillance state as a “real and present threat” rather than a distant concern.

During a televised discussion, Takaichi emphasized that Japan should not treat China as a normal economic partner when it openly detains foreign nationals under vague laws. She urged the government and businesses to avoid unnecessary exposure by refraining from purchasing Chinese-made drones or surveillance equipment. Her position reflects a broader shift within the Japanese Cabinet toward prioritizing national security over short-term economic convenience.

Meanwhile, Takahashi highlighted the risk of technological infiltration through software and network systems. He warned that even seemingly harmless services—such as Tencent’s cloud solutions or Alibaba’s data centers—could act as “digital backdoors” for information gathering. According to him, Japan’s overreliance on foreign tech infrastructure creates a “hidden vulnerability” that adversaries could exploit during diplomatic or economic tensions.

Both experts have also called for stronger legislation, including a comprehensive Anti-Spy Law that criminalizes espionage and protects domestic industries from data theft. Their stance is gaining traction among policymakers, who increasingly view cybersecurity as a cornerstone of Japan’s national defense.

Ultimately, Takaichi and Takahashi’s warnings have helped push Japan’s national conversation toward digital sovereignty, emphasizing that security must come before convenience in an era dominated by global surveillance.

Japan Faces a New Wave of Surveillance Risks

Across Japan, thousands of surveillance cameras and commercial drones are quietly collecting visual and geographic data every day. While these technologies enhance convenience and public safety, their origins have raised growing concern among security experts. Many of these devices are produced by Chinese manufacturers, such as Hikvision and DJI, both of which have been linked to China’s state surveillance apparatus.

Hikvision cameras, for example, are widely used in Japanese shopping malls, parking lots, and even some government buildings. Experts warn that these systems could transmit footage or metadata to servers located in China, potentially enabling foreign monitoring of sensitive sites. Although there is no direct evidence of widespread misuse, the risk remains substantial enough to prompt official caution from Japan’s Ministry of Defense.

Similarly, Chinese-made drones—commonly employed for infrastructure inspections and agriculture—are now under scrutiny. Drones from DJI and other Chinese firms have been restricted by the U.S. and several European nations due to security concerns. Japan is following suit, encouraging local governments and corporations to purchase domestically produced alternatives to protect aerial mapping and surveillance data.

Data centers represent another layer of risk. Companies like Tencent and Alibaba have established facilities in Japan that store enormous amounts of cloud data. If Chinese authorities compel these firms to share information, even data physically stored on Japanese soil could be accessed abroad. This blurs the boundary between national and foreign digital territory.

In response, Japanese lawmakers are considering new regulations that would require transparency about the origin and security standards of surveillance and data technologies. The goal is not to isolate Japan from global innovation, but to ensure that national security and citizens’ privacy are not compromised by hidden technological dependencies.

Japan’s Efforts to Strengthen Its National Security Framework

Japan is now accelerating discussions on a comprehensive Anti-Spy Law designed to protect the nation from information leaks and foreign espionage. For years, policymakers have debated whether Japan should adopt stronger intelligence-related legislation similar to those in the United States or the United Kingdom. Recent detentions of Japanese nationals in China and concerns over digital infiltration have finally pushed this issue to the top of the political agenda.

Currently, Japan lacks a unified law that directly addresses espionage or data theft. Existing legal frameworks, such as the State Secrets Protection Act and Cybersecurity Basic Act, offer only partial coverage. Security experts argue that without a dedicated Anti-Spy Law, Japan remains vulnerable to cyberattacks, data breaches, and covert foreign influence.

The proposed legislation would criminalize unauthorized data sharing, mandate stricter vetting of foreign technology suppliers, and empower authorities to investigate espionage cases more effectively. Supporters believe this would help Japan safeguard sensitive military, industrial, and digital assets from external manipulation. Critics, however, caution that the law must include clear definitions to prevent misuse or restrictions on freedom of expression.

Alongside the legal reforms, Japan is also investing heavily in domestic technology development. The government has introduced subsidies for Japanese-made drones, AI systems, and cloud infrastructure to reduce reliance on Chinese suppliers. Corporations like NEC and Fujitsu are emerging as key players in building a more secure national tech ecosystem.

Ultimately, Japan’s twin strategy—legislative reform and technological independence—reflects its commitment to protecting sovereignty in the digital age. As global tensions intensify, the country is moving decisively toward a future where national security and innovation coexist.

Japan’s Path Toward Digital Sovereignty and National Security

Japan’s growing awareness of the risks posed by Chinese technology marks a significant shift in its national security strategy. The warnings from experts such as Sanae Takaichi and Yoichi Takahashi have sparked a broader public conversation about data protection, surveillance, and the country’s dependence on foreign-made digital infrastructure. These discussions are no longer just political; they have become a national priority.

As China expands its global surveillance capabilities through companies like Tencent, Alibaba, and Huawei, Japan faces the challenge of protecting its digital borders without isolating itself from global innovation. Achieving this balance requires strong legislation, transparent governance, and sustained investment in domestic technology.

The introduction of a comprehensive Anti-Spy Law could serve as the cornerstone of Japan’s security framework. Coupled with the promotion of domestic AI, cloud, and drone industries, it represents a proactive step toward achieving true digital sovereignty. Such reforms would not only strengthen national defense but also enhance the global competitiveness of Japan’s technology sector.

However, success will depend on collaboration between government, business, and academia. Public awareness campaigns about data safety and the importance of using trusted technologies will play an equally vital role. Japan’s experience may even serve as a model for other nations navigating the complex intersection of security, innovation, and international cooperation.

In the end, Japan’s pursuit of a safer digital future is not just about protecting data—it is about preserving independence, trust, and the values that define a free and open society in the 21st century.

Related Reading:

ディスカッション

コメント一覧

まだ、コメントがありません