Japan Sets Immigration Quota Under Takaichi

Introduction: The Background of the Takaichi Administration and the “Foreign Resident Quota System”

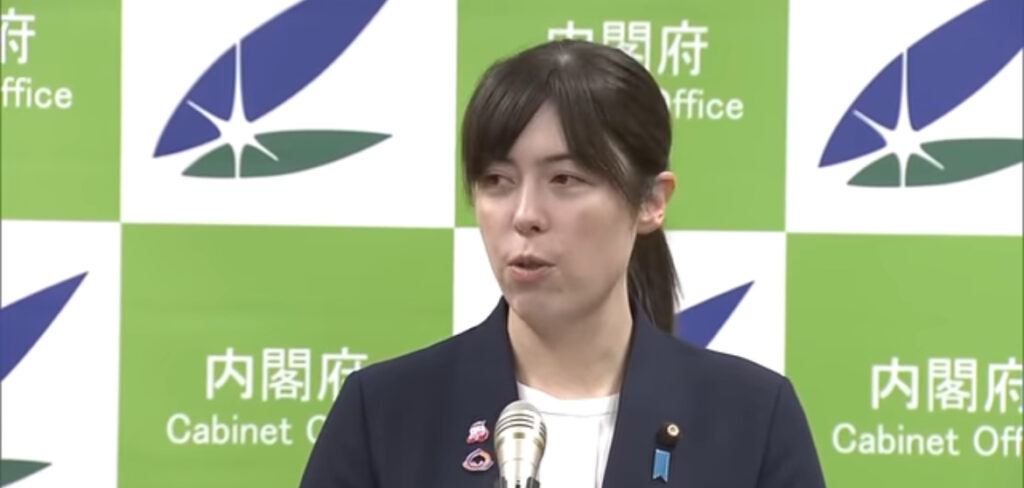

As Japan enters 2025, the political landscape is witnessing a major shift under Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi. Among the policy concepts gaining attention is the proposed “foreign resident quota system”—a framework designed to regulate the total number of foreign nationals allowed to live and work in Japan. This marks a potential turning point in Japan’s postwar immigration policy, raising fundamental questions about national identity, labor policy, and demographic sustainability.

Japan has long struggled with a declining birthrate and an aging population. The shortage of workers in sectors such as construction, caregiving, and agriculture has pushed the government to expand visa programs and accept more foreign workers over the past decade. However, critics argue that the country’s current system lacks long-term planning and social integration measures. In this context, the idea of a quota-based management model has emerged as a possible solution to balance economic needs with social stability.

The Takaichi administration is expected to introduce this concept as part of a broader agenda of “national resilience and economic self-defense.” Supporters see it as a pragmatic approach to protect the domestic workforce while maintaining controlled immigration levels. Opponents, however, fear that such a system may reinforce exclusionary tendencies and harm Japan’s international image as an open and cooperative society.

At its core, the debate over the foreign resident quota system reflects a deeper dilemma: How can Japan sustain its economy and cultural cohesion in a rapidly globalizing world? As the new administration seeks to redefine Japan’s position in the global labor market, the discussion surrounding foreign population limits is set to become one of the most critical political issues of the decade.

In the following sections, this article explores the historical, economic, and ethical dimensions of the quota proposal—analyzing its feasibility, potential consequences, and the lessons Japan can learn from other nations’ experiences.

Japan’s Labor Shortage and the Aging Society

Japan’s labor market is facing an unprecedented crisis. The working-age population—those aged 15 to 64—has been shrinking for over two decades. According to government data, it is projected to drop below 70 million by 2035, representing a loss of nearly one-fifth of the workforce compared to 2000. This demographic decline has triggered chronic labor shortages across key industries, threatening the foundation of Japan’s economic stability.

In sectors such as construction, caregiving, manufacturing, and agriculture, the shortage of workers has become a national emergency. Companies have struggled to fill positions even with wage increases and automation. In rural areas, the lack of young workers has accelerated the collapse of local economies. The government has responded by expanding visa programs like the “Specified Skilled Worker” system, which allows foreign nationals to work in designated industries. Yet, these measures have failed to solve the structural imbalance between supply and demand.

The heart of the issue lies in Japan’s demographic pyramid. With a median age above 49, the country now ranks among the oldest populations in the world. More than 28 percent of citizens are aged 65 or older, while birth rates remain below replacement level at 1.3. This means that even aggressive immigration or automation policies will struggle to offset the declining labor base. The economic consequences are already visible: slowing GDP growth, increased social welfare costs, and rising dependency ratios.

Foreign workers have become an essential support pillar for Japan’s economy. In 2025, the number of registered foreign workers surpassed 2 million, double the figure from a decade earlier. They are concentrated in sectors like nursing, logistics, and hospitality—industries most affected by demographic decline. However, the rapid increase in foreign labor has sparked debates over integration, fair treatment, and the long-term sustainability of such reliance. Many policymakers now argue that Japan needs a more strategic approach, not just short-term labor imports.

These pressures form the backdrop to the Takaichi administration’s proposal for a foreign resident quota system. The idea is not only to control numbers but to design a sustainable mechanism for balancing population, productivity, and social cohesion. In essence, it is a response to the limits of Japan’s demographic model—and a sign that the country must redefine how it manages both its people and its future workforce.

The Purpose and Framework of the Foreign Resident Quota System

The proposed foreign resident quota system under the Takaichi administration represents a new approach to immigration governance in Japan. Rather than an open-ended system based on employer demand, the policy aims to establish a national framework that caps the total number of foreign residents according to demographic, economic, and social indicators. This marks a shift from a reactive immigration model to a strategic population management policy.

The main goal of the quota system is to create a balance between Japan’s economic needs and its social capacity to integrate newcomers. By introducing an annual or multi-year cap, the government seeks to prevent sudden population surges and ensure that local infrastructure—such as housing, education, and healthcare—can adapt. The idea is to manage immigration not as an emergency response to labor shortages, but as a controlled and predictable process aligned with Japan’s long-term national interests.

According to early policy drafts discussed within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, the system would classify foreign residents into categories such as “skilled professionals,” “essential labor,” and “students.” Each category would have separate quotas based on labor market data and regional demand. For example, construction and caregiving sectors might receive higher allocations, while other fields could face stricter limits. A central digital registry would track residency permits in real time, allowing authorities to monitor compliance and adjust yearly quotas accordingly.

The system also emphasizes security and accountability. Applicants would undergo enhanced background checks, and companies employing foreign workers would be required to register under a transparent certification program. This aims to reduce illegal employment and protect workers from exploitation—issues that have plagued Japan’s existing Technical Intern Training Program. Additionally, local governments would play a greater role in monitoring social integration, providing language education, and ensuring equal access to basic services.

Supporters of the policy argue that it would strengthen national sovereignty and restore public confidence in immigration management. They view it as a pragmatic evolution of Japan’s immigration framework, not a step backward. Critics, however, warn that a rigid quota system could discourage global talent and undermine Japan’s international competitiveness. As debate intensifies, the Takaichi administration must balance control with openness—creating an immigration model that secures Japan’s future without isolating it from the global community.

Support and Opposition — A Nation Divided over Immigration Limits

The debate surrounding Japan’s proposed foreign resident quota system has revealed a deep divide in public opinion. Supporters see the policy as a necessary safeguard for Japan’s social stability and national identity, while opponents warn it could fuel xenophobia and damage the nation’s global reputation. The discussion has evolved beyond simple numbers—it now reflects Japan’s struggle to redefine who belongs in its future society.

Among conservative circles and nationalist commentators, the quota system has been welcomed as a long-overdue reform. Many argue that Japan must protect its social cohesion before opening its doors wider to immigration. They believe a clearly defined limit will prevent cultural friction, reduce welfare burdens, and preserve public order. The Takaichi administration’s emphasis on “managed integration” resonates strongly with voters concerned about rising crime, illegal overstays, and perceived social fragmentation in urban areas.

Business leaders, however, express mixed feelings. While they understand the need for social stability, Japan’s corporate sector depends heavily on foreign workers to sustain production. The construction and service industries, in particular, warn that strict quotas could deepen labor shortages and stall economic recovery. Several business federations have urged the government to design a flexible system that adjusts quotas based on economic data, not ideology. For them, immigration policy is not about ideology—it is about survival.

Human rights organizations and progressive policymakers have voiced stronger opposition. They argue that limiting foreign residents through numerical caps risks institutionalizing discrimination and undermining Japan’s commitments to international human rights treaties. Advocacy groups stress that integration should focus on equal treatment and opportunity, not population control. Many also highlight the moral contradiction between Japan’s dependence on foreign labor and its reluctance to offer permanent residency or family unification options.

The media landscape mirrors this polarization. Conservative outlets frame the quota as a responsible step toward national renewal, while liberal publications warn of a “closed Japan” narrative reminiscent of the prewar era. On social media, debates have grown increasingly emotional, with hashtags like #ProtectJapan and #OpenJapan symbolizing the ideological split. Despite the tensions, one fact is clear: the question of how many foreigners Japan should accept has become a defining issue of the Takaichi era, shaping not only policy but also Japan’s collective identity in the 21st century.

Global Comparisons — Lessons from Other Countries’ Immigration Systems

To understand Japan’s proposed foreign resident quota system, it is essential to look abroad. Several developed nations have already implemented similar population control or skilled migration frameworks, offering valuable lessons on how numerical caps can affect economic growth, integration, and national identity. The international experience reveals both the strengths and pitfalls of a quota-based approach.

Germany, for example, operates a managed migration system tied closely to labor market demand. After the 2015 refugee crisis, Berlin introduced stricter entry thresholds while expanding skilled worker programs. The result has been a more balanced approach—welcoming talent while controlling entry volumes. However, integration challenges remain significant, as linguistic and cultural gaps continue to strain local communities. Japan could learn from Germany’s dual strategy: strict control combined with robust social integration policies.

Canada, often praised for its merit-based immigration model, applies a point system rather than strict quotas. Applicants are assessed based on education, language ability, and work experience. This system allows flexibility while maintaining quality control. Canada’s success lies in its ability to link immigration policy directly with economic development goals. For Japan, adopting a points-based mechanism within a quota framework could create a hybrid model—one that prioritizes talent while preserving predictability.

South Korea provides a more cautionary tale. Facing similar demographic pressures, Seoul introduced temporary worker programs with rigid numerical limits. While effective in curbing uncontrolled inflows, these policies also created labor shortages and social inequality. Many foreign workers remain stuck in low-wage positions without clear paths to residency or integration. Japan must avoid repeating this pattern by ensuring that quotas do not trap workers in a revolving-door system of temporary labor.

In France, strict immigration caps have historically sparked social tension and political polarization. Periodic tightening of migration laws often backfired, leading to protests and widening cultural divides. The lesson here is that immigration management cannot succeed without social consensus and transparent communication. Japan’s policymakers will need to engage citizens in open dialogue, emphasizing how controlled immigration contributes to national renewal, not division.

Each of these cases demonstrates that numbers alone cannot define successful immigration policy. The effectiveness of a quota system depends on context—its flexibility, transparency, and fairness. As Japan considers its own path under the Takaichi administration, learning from both Western and Asian experiences could help build a model that balances control with compassion, ensuring economic resilience and social harmony in the decades to come.

Economic and Social Impacts — The Short and Long-Term Effects of the Quota System

The introduction of a foreign resident quota system under the Takaichi administration could reshape Japan’s economy and society for decades. In the short term, the policy would influence labor availability, wage levels, and industrial productivity. Over the long term, it could redefine Japan’s demographic composition, social cohesion, and global competitiveness. Understanding both dimensions is essential for designing a sustainable immigration framework.

Economically, the quota system could tighten labor supply in low-wage sectors such as agriculture, caregiving, and manufacturing. Companies reliant on foreign workers may face higher operational costs and slower output. Some analysts predict that limiting inflows could raise wages for domestic workers, partially offsetting the negative effects. However, excessive restrictions risk shrinking entire industries and accelerating automation before Japan’s workforce and infrastructure are ready to adapt.

In the medium term, the policy may encourage businesses to invest more aggressively in technology. Robotics, artificial intelligence, and digital transformation are already central to Japan’s productivity strategy. A controlled labor inflow could push firms to innovate faster, reducing dependence on manual labor. Yet, innovation without inclusion carries social costs: if communities lack diversity or intercultural understanding, Japan may lose the global talent needed to sustain creativity and economic dynamism.

Socially, the quota system presents both opportunities and risks. Supporters argue that it can promote better integration by matching immigration levels with local capacity. Schools, healthcare institutions, and housing markets would have time to adjust, ensuring smoother adaptation for both residents and newcomers. A stable pace of immigration can help avoid cultural shock and maintain public trust in government management.

However, critics warn that numerical caps might reinforce stereotypes or create barriers to long-term inclusion. Limiting foreign residents too strictly could isolate immigrant communities, making integration even harder. Public perception also matters—if quotas are framed as “restrictions,” they may trigger xenophobic sentiment. Conversely, if presented as a “strategic management tool,” they can enhance transparency and public confidence in immigration policy.

In the long run, Japan’s global competitiveness will depend on how well it balances these forces. A flexible quota system—responsive to economic data, human rights standards, and demographic trends—could help stabilize the labor market while maintaining social harmony. But rigidity or political manipulation could lead to stagnation. The success of this policy will not be measured by how few foreigners Japan accepts, but by how effectively it integrates those who choose to call Japan home.

Conclusion — Japan’s Path Forward and Policy Recommendations

The debate over Japan’s foreign resident quota system marks a defining moment in the country’s approach to population management and national identity. As the Takaichi administration seeks to balance economic necessity with social cohesion, the path forward must emphasize strategy over sentiment. Japan stands at a crossroads: it can either treat immigration as a defensive issue or embrace it as a tool for sustainable growth and renewal.

First, Japan needs to frame the quota system as a strategic management model—not as a barrier. By linking quota levels to transparent economic indicators such as GDP growth, labor shortages, and regional demand, policymakers can ensure flexibility while maintaining public trust. The system should be dynamic, allowing adjustments when industries face unexpected pressures or when integration outcomes improve.

Second, integration policies must evolve alongside numerical limits. Language training, local community programs, and workplace inclusion initiatives are essential for building long-term cohesion. Without these, quotas risk creating temporary, isolated labor communities. Japan can learn from Canada’s and Germany’s integration frameworks, where cultural orientation and family inclusion are key to stability and loyalty among immigrants.

Third, the government must prioritize transparency and data-based policymaking. Real-time population tracking, public reporting, and academic partnerships can make the system accountable. A trusted information platform will prevent misinformation and foster informed public discussion. In this sense, effective communication is as important as policy design itself.

Finally, Japan should embrace immigration as part of a broader demographic strategy—not as a last resort. A well-calibrated quota system can coexist with innovation, gender equality initiatives, and family support programs aimed at boosting the native birthrate. The ultimate goal is not to replace Japan’s population but to sustain its vitality in a rapidly changing global environment.

As Japan faces the challenges of the mid-21st century, the question is no longer whether to accept foreign workers, but how to manage migration wisely and humanely. If the Takaichi administration succeeds in creating a balanced, transparent, and forward-looking quota policy, Japan could pioneer a new model of population governance—one that protects its traditions while preparing for a shared global future.

ディスカッション

コメント一覧

まだ、コメントがありません